In this post we will discuss a simple Advent-of-Code style problem that shouldn't take programmers much effort in any programming language.

Like Advent-of-Code, the problem consists of two parts: a trivial one and an easy one.

Part A: The trivial part

We're going to concern ourselves with finding elements in the Fibonacci sequence whose decimal representations contain certain substrings:

fibs = 1 : 1 : zipWith (+) fibs (tail fibs)

findFibWith substr = find (isInfixOf substr . show) fibsWe'll look for substrings like "11235813", which is a concatenation of the first elements in the fibonacci sequence, and compute the first 8 digits of the element which contains this substring.

Or in simple Haskell terms:

partA n =

take 8 (show result)

where

firstFibs = take n fibs >>= show

Just result = findFibWith firstFibsNo problem so far :)

Part B: Shouldn't be tricky

We're going to take the result of part A, and find the first fibonacci element to contain it, and take its first 8 digits,

Or in simple Haskell terms:

partB n =

take 8 (show result)

where

Just result = findFibWith (partA n)But here comes the tricky part: the above code has a "space leak".

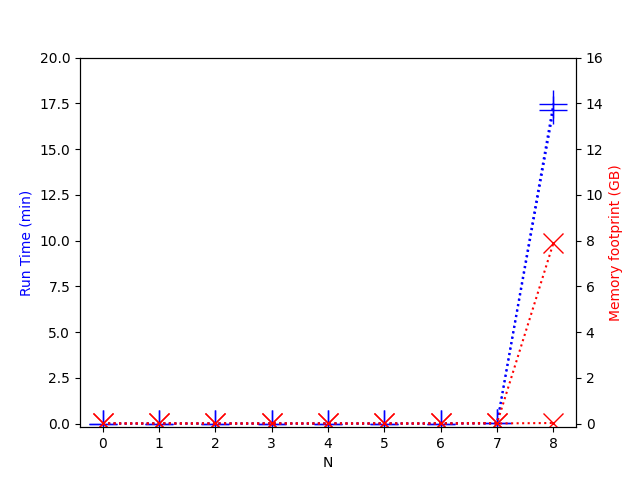

If we plot the run times and memory footprints of separate runs computing part A and part B, a disturbing picture is revealed:

For part A the memory footprint stayed low, but for part B the memory footprint grew linearly with the running time!

Spoiler alert: If you want to solve this challenge on your own, pause and do it before reading the analysis and work-arounds in the next sections.

Analysing the space leak

The irony of the situation is that when we research when exactly the

memory footprint grew so much, we will find that it was happening when

computing partA, but only when partB was going

to follow it!

This is because the mere future use of findFibWith in

partB holds on to fibs to re-use it later,

rather than letting the garbage collector rid of it.

This memoization of the fibonacci sequence, which we get for free thanks to Haskell's pervasive lazy evaluation, is something that in this situation we'd rather avoid.

Working around the problem

An obvious but silly workaround is employing deliberate code

duplication, with findFibWith2 using fibs2 and

thus not retaining fibs. However we'd like a more

ecological solution than single-use functions, so we'll look for a

different work-around.

What we can do is to rewrite findFibWith so that

fibs is woven into it such that the series is never stored

in a data structure:

findFibWith substr =

go 1 1

where

go cur next

| isInfixOf substr (show cur) = Just cur

| otherwise = go next (cur + next)Comparison: Functional Rust

We'll compare the above situation to using Rust in a functional manner, and make an implementation which is mostly a translation of the Haskell implementation above.

use itertools::iterate;

use num_bigint::BigUint;

use num_traits::One;

use std::env;

fn fibs() -> impl Iterator<Item = BigUint> {

iterate(

(One::one(), One::one()),

|(cur, next): &(BigUint, BigUint)| (next.clone(), cur + next),

)

.map(|(cur, _)| cur)

}

fn find_fib_with(substr: &str) -> Option<BigUint> {

fibs().find(|x| x.to_string().contains(&substr))

}

fn part_a(n: usize) -> String {

let first_fibs = fibs()

.take(n)

.map(|x| x.to_string())

.collect::<Vec<_>>()

.concat();

String::from(&find_fib_with(&first_fibs).unwrap().to_string()[..8])

}

fn part_b(n: usize) -> String {

String::from(&find_fib_with(&part_a(n)).unwrap().to_string()[..8])

}

fn main() {

let n = env::args().nth(1).and_then(|x| x.parse().ok()).unwrap_or(7);

println!("{}", part_b(n));

}In this implementation we wrote modular code in a straight-forward manner, like we first tried to do in Haskell, and it just worked, without any space leaks.

(btw a more efficient Rust implementation can probably be made employing mutability for constant factor gains, but in this post we don't concern ourselves with constant factors)

Follow-up question

In light of this example, do you think that pervasive laziness helps us write modular and re-usable code, or is it a hindrance to it?

Notes

- Header image was generated with DALL-E. I attempted using it to visualize "space leaks".

- This post is my second attempt at making an argument about pervasive lazy evaluation. My previous attempt appears to have failed convincing the people in r/haskell. I hope that this post better demonstrates the problem

- Discussion:

r/haskell

- I've summarized solutions/work-arounds from this discussion into a new post